- Home

- H. Beam Piper

The H. Beam Piper Megapack

The H. Beam Piper Megapack Read online

COPYRIGHT INFO

The H. Beam Megapack is copyright © 2013 by Wildside Press LLC.

* * * *

“Time and Time Again” originally appeared in Astounding Science Fiction, April 1947.

“He Walked Around the Horses” originally appeared in Astounding Science Fiction, April 1948.

“Police Operation” originally appeared in Astounding Science Fiction, July 1948.

“The Mercenaries” originally appeared in Astounding Science Fiction, March, 1950.

“Last Enemy” originally appeared in Astounding Science Fiction, August, 1950.

“Flight From Tomorrow” originally appeared in Science Fiction Stories, September/October 1950.

“Operation R.S.V.P.,” originally appeared in Amazing Stories, January, 1951.

“Dearest” originally appeared in Weird Tales, March 1951.

“Temple Trouble” originally appeared in Astounding Science Fiction, April, 1951.

“Genesis” originally appeared in Future Combined with Science Fiction Stories, September 1951.

“Day of the Moron” originally appeared in Astounding Science Fiction, September 1951.

Uller Uprising originally appeared in 1952.

Null-ABC originally appeared in Astounding Science Fiction as a two-part serial in February and March, 1953.

“The Return” originally appeared in Astounding Science Fiction, January, 1954.

“Time Crime” originally appeared in Astounding Science Fiction Magazine as a 2-part serial, February and March 1955.

“Omnilingual” originally appeared in Astounding Science Fiction, February, 1957.

“The Edge of the Knife” originally appeared in Amazing Stories, May 1957.

“The Keeper” originally appeared in Venture Science Fiction, July 1957.

“Graveyard of Dreams” originally appeared in Galaxy Magazine, February 1958.

“Ministry of Disturbance” originally appeared in Astounding Science Fiction, December 1958.

“Hunter Patrol” originally appeared in Amazing Stories, May 1959.

“Crossroads of Destiny” originally appeared in Fantastic Universe Science Fiction, July 1959.

“The Answer” originally appeared in Fantastic Universe Science Fiction, December, 1959.

“Oomphel in the Sky” originally appeared in Analog Science Fact—Science Fiction, November 1960.

Four-Day Planet originally appeared in 1961.

“Naudsonce” originally appeared in Analog Science Fact—Science Fiction, January 1962.

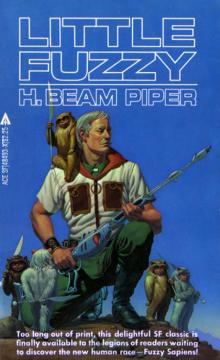

Little Fuzzy originally appeared in 1962

“A Slave is a Slave” originally appeared in Analog Science Fact—Science Fiction, April 1962.

Space Viking originally appeared in Analog Science Fact—Science Fiction as a 4-part serial, in November 1962, December 1962, January 1963, and February 1963.

The Cosmic Computer originally appeared in 1963.

“Rebel Raider” originally appeared in True: The Man’s Magazine, December 1950.

Murder in the Gunroom originally appeared in 1953.

A NOTE FROM THE PUBLISHER

Over the last year, our “Megapack” series of ebook anthologies has proved to be one of our most popular endeavors. (Maybe it helps that we sometimes offer them as premiums to our mailing list!) One question we keep getting asked is, “Who’s the editor?”

The Megapacks (except where specifically credited) are a group effort. Everyone at Wildside works on them. This includes John Betancourt, Carla Coupe, Steve Coupe, Bonner Menking, Colin Azariah-Kribbs, A.E. Warren, and many of Wildside’s authors…who often suggest stories to include (and not just their own!).

A NOTE FOR KINDLE READERS

The Kindle versions of our Megapacks employ active tables of contents for easy navigation…please look for one before writing reviews on Amazon that complain about the lack! (They are sometimes at the ends of ebooks, depending on your reader.)

RECOMMEND A FAVORITE STORY?

Do you know a great classic science fiction story, or have a favorite author whom you believe is perfect for the Megapack series? We’d love your suggestions! You can post them on our message board at http://movies.ning.com/forum (there is an area for Wildside Press comments).

Note: we only consider stories that have already been professionally published. This is not a market for new works.

TYPOS

Unfortunately, as hard as we try, a few typos do slip through. We update our ebooks periodically, so make sure you have the current version (or download a fresh copy if it’s been sitting in your ebook reader for months.) It may have already been updated.

If you spot a new typo, please let us know. We’ll fix it for everyone. You can email the publisher at [email protected] or use the message boards above.

—John Betancourt

Publisher, Wildside Press LLC

www.wildsidepress.com

THE MEGAPACK SERIES

The Adventure Megapack

The Christmas Megapack

The Second Christmas Megapack

The Cowboy Megapack

The Craig Kennedy Scientific Detective Megapack

The Cthulhu Mythos Megapack

The Ghost Story Megapack

The Horror Megapack

The Macabre Megapack

The Martian Megapack

The Military Megapack

The Mummy Megapack

The Mystery Megapack

The Science Fiction Megapack

The Second Science Fiction Megapack

The Third Science Fiction Megapack

The Fourth Science Fiction Megapack

The Fifth Science Fiction Megapack

The Sixth Science Fiction Megapack

The Penny Parker Megapack

The Pinocchio Megapack

The Pulp Fiction Megapack

The Rover Boys Megapack

The Steampunk Megapack

The Tom Corbett, Space Cadet Megapack

The Tom Swift Megapack

The Vampire Megapack

The Victorian Mystery Megapack

The Werewolf Megapack

The Western Megapack

The Wizard of Oz Megapack

AUTHOR MEGAPACKS

The B.M. Bower Megapack

The Wilkie Collins Megapack

The Randall Garrett Megapack

The Murray Leinster Megapack

The Second Murray Leinster Megapack

The Andre Norton Megapack

The H. Beam Piper Megapack

The Rafael Sabatini Megapack

INTRODUCTION: MEET H. BEAM PIPER

Henry Beam Piper (March 23, 1904 – c. November 6, 1964) was an American science fiction author. He wrote many short stories and several novels. He is best known for his extensive “Terro-Human Future History” series of stories and a shorter series of “Paratime” alternate history tales. He wrote under the name H. Beam Piper.

Piper was largely self-educated; he obtained his knowledge of science and history “without subjecting myself to the ridiculous misery of four years in the uncomfortable confines of a raccoon coat.” He went to work at age 18 as a laborer at the Pennsylvania Railroad’s Altoona yards in Altoona, Pennsylvania. He also worked as a night watchman for the railroad.

Piper published his first short story, “Time and Time Again”, in 1947 in Astounding Science Fiction; it was adapted for the radio program Dimension X and first broadcast in 1951, and was re-produced for X Minus One in 1956. He was primarily a short story author until 1961, when he made a productive, if short-lived, foray into novels. He collected guns and also wrote one mystery, Murder in the Gunroom.

He committed suicide in November 1964 in Williamsport, Pen

nsylvania, bringing his career to a premature conclusion. The exact date of his death is unknown; the last entry in his diary was dated November 5 (“Rain 0930”), and the date his body was found is reported as November 9 or November 11 by various sources. According to Jerry Pournelle’s introduction to Little Fuzzy, Piper shut off all the utilities to his apartment, put painter’s drop-cloths over the walls and floor, and took his own life with a handgun from his collection. In his suicide note, he gave an explanation that “I don’t like to leave messes when I go away, but if I could have cleaned up any of this mess, I wouldn’t be going away. H. Beam Piper’”

* * * *

Some biographers attribute his act to financial problems, others to family problems; Pournelle wrote that Piper felt burdened by financial hardships in the wake of a divorce, and the mistaken perception that his career was foundering (his agent had died without notifying him of multiple sales). Editor George H. Scithers, who knew Piper socially, has stated that Piper wanted to spite the ex-wife he despised: by committing suicide, Piper voided his life insurance policy and prevented her from collecting.

An unpublished story, “Only the Arquebus”, has gone missing since his suicide; it is probable that he destroyed it along with many of his personal papers.

His output was eventually purchased by Ace Science Fiction and reprinted in a set of paperbacks in the early 1980s. Many of these have since gone out of print, though his two best-known arcs were again reprinted by Ace in 1998 and 2001. Late in his career, Piper corresponded with Pournelle, who was the Ace editor who helped reprint some of his novels.

THEMES AND HALLMARKS

Piper’s stories fall into two camps: stark space opera, such as Space Viking, or stories of cultural conflict or misunderstanding, such as Little Fuzzy or the Paratime stories.

A running theme in his work is that history repeats itself; past events will have direct and clear analogues in the future. The novel Uller Uprising is the clearest example of this, being based on the Sepoy Mutiny. A similarly clear example is the very name of Space Viking; although that novel is not a direct reinterpretation of a specific historical precedent, a later theme in the book involves the takeover of a planet in a manner reminiscent of the rise of Adolf Hitler.

Piper’s characterization was rooted in the notion of the self-reliant man: an individual able to take care of himself and both willing and able to tackle any situation which might arise. This is perfectly exemplified in a bit of dialogue found in his short story “Oomphel in the Sky” (1960):

“He actually knows what has to be done and how to do it, and he’s going right ahead and doing it, without holding a dozen conferences and round-table discussions and giving everybody a fair and equal chance to foul things up for him.”

As a result, his yarns tend towards the heroic, and the conflict is usually driven externally.

Piper was also interested in General Semantics. It is explicitly mentioned in Murder in the Gunroom, and its principles, such as awareness of the limitations of knowledge, are apparent in his later work.

IMPACT

Piper did not live to see how influential he was to other science fiction writers.

Michael McCollum’s first novel, A Greater Infinity, was inspired by Piper’s notion of the Paratime Police (and to a lesser extent by Isaac Asimov’s The End of Eternity). The Paradox Patrol, in a series of stories by F. Gwynplaine MacIntyre published in Analog Science Fiction and Fact, are a parody of Piper’s Paratime Police, although they also pay homage to Alfred Bester in their enforcement of “Bester’s Law”.

Robert Adams’ Castaways in Time is similar in many ways to Piper’s Lord Kalvan of Otherwhen. Adams’ book has a group of late-1970s Americans transported to an alternate medieval England where the Roman Catholic Church controls the supply of gunpowder. Jerry Pournelle’s Janissaries series is an obvious tribute to Lord Kalvan, with several early scenes being very close echoes of scenes in Piper’s work. Charles Stross’s Merchant Princes series explicitly acknowledges H. Beam Piper’s Paratime as an influence.

Piper’s story “Omnilingual” has been much reprinted and has been referred to in many subsequent stories dealing with the translation of alien languages.

Elizabeth Bear has stated that her novel Undertow was inspired by Little Fuzzy.

MAJOR STORYLINES

Terro-Human Future History

The Terro-Human Future History is Piper’s detailed account of the next 6000 years of human history. 1942, the year the first fission reactor was constructed, is defined as the year 1 A.E. (Atomic Era). In 1973, a nuclear war devastates the planet, eventually laying the groundwork for the emergence of a Terran Federation, once humanity goes into space and develops antigravity technology.

The story “The Edge of the Knife” occurs slightly before the war, and involves a man who sees flashes of the future. It links many key elements of Piper’s series.

Most of the stories take place during the next millennium, during the age of the two Federations. Most notable among these novels are the three Fuzzy novels (starting with Little Fuzzy), which concern the recognition of a peculiar alien species as sapient, and the efforts of the two species to learn to live together on the Fuzzies’ home world of Zarathustra.

The Federation collapses in the System States War and following Interstellar Wars (a bit of which can be seen in The Cosmic Computer), leading to a lengthy interregnum, during which there is no central human power. Space Viking is set in this chaotic period.

The interregnum ends with the founding of the first Empire. At least five empires rule humanity during the next four thousand years, but only a handful of short stories (collected in Empire) depict this period. Piper generally portrays these empires as benign, ruled by enlightened despots.

Piper’s future history resemble in some ways Isaac Asimov’s Foundation Trilogy, and was probably influenced by it, especially since both authors wrote for John W. Campbell.

Paratime

A much shorter series of alternate history stories is Piper’s Paratime sequence, which includes the novel Lord Kalvan of Otherwhen. These stories concern the Paratime Police, a law enforcement outfit from a parallel world which has learned how to move between timelines. They jealously guard the secret, even as they mine other worlds for their resources. Notably, it appears that humans are in fact Martian refugees who escaped a calamity on their home planet and migrated to Earth.

Unlike many alternate histories, these stories tend to focus on points of divergence far back in the past. For instance, Lord Kalvan involves a police officer who is accidentally transported to a world where the ancestors of modern Europeans failed to move into Europe. Instead, the nomadic tribes migrated across Asia and into North America. The people living on the eastern coast of North American in this novel settled the area from the west, and still live in a medieval society.

Many readers point towards the short story “Genesis” to suggest that the Terro-Human Future History universe is in fact an alternate world in the Paratime universe, where the Martians’ escape from Mars resulted in their forgetting their heritage and having to start over. However, in several letters to friends and in an article published in a fan magazine, Piper himself listed the true Paratime stories, and he never identified “Genesis” as one.

By the same token, in spite of Piper’s lack of explicit stipulation, it is appropriate to contend that “Omnilingual” (1957)—which concerns a near-future scientific expedition to Mars under the aegis of an international Earth government—is also a Paratime story. The scientists and scholars involved in this effort are found in media res excavating the ruins of the advanced human civilization which had been gradually destroyed on the fourth planet some 50,000 years before. It should be noted that in “Omnilingual” there is no mention of the northern hemisphere’s thermonuclear devastation as a result of the NATO/Communist “cold war” kindled into an orgy of extermination by the impact of an antimatter meteorite, which was detailed by Piper in his story “The Answer�

�� (1959). Throughout the Terro-Human Future History, that conflict and the destruction wrought across the nations of the First and Second Worlds is pervasive as an explanation of the precise manner in which the home planet’s culture (by way of South America, Australia, and South Africa in particular) comes to influence the planets of Piper’s Federation and Empire.

TIME AND TIME AGAIN (1947)

Blinded by the bomb-flash and numbed by the narcotic injection, he could not estimate the extent of his injuries, but he knew that he was dying. Around him, in the darkness, voices sounded as through a thick wall.

“They mighta left mosta these Joes where they was. Half of them won’t even last till the truck comes.”

“No matter; so long as they’re alive, they must be treated,” another voice, crisp and cultivated, rebuked. “Better start taking names, while we’re waiting.”

“Yes, sir.” Fingers fumbled at his identity badge. “Hartley, Allan; Captain, G5, Chem. Research AN/73/D. Serial, SO-23869403J.”

“Allan Hartley!” The medic officer spoke in shocked surprise. “Why, he’s the man who wrote Children of the Mist, Rose of Death, and Conqueror’s Road!”

He tried to speak, and must have stirred; the corpsman’s voice sharpened.

“Major, I think he’s part conscious. Mebbe I better give him ’nother shot.”

“Yes, yes; by all means, sergeant.”

Something jabbed Allan Hartley in the back of the neck. Soft billows of oblivion closed in upon him, and all that remained to him was a tiny spark of awareness, glowing alone and lost in a great darkness.

* * * *

The Spark grew brighter. He was more than a something that merely knew that it existed. He was a man, and he had a name, and a military rank, and memories. Memories of the searing blue-green flash, and of what he had been doing outside the shelter the moment before, and memories of the month-long siege, and of the retreat from the north, and memories of the days before the War, back to the time when he had been little Allan Hartley, a schoolboy, the son of a successful lawyer, in Williamsport, Pennsylvania.

His mother he could not remember; there was only a vague impression of the house full of people who had tried to comfort him for something he could not understand. But he remembered the old German woman who had kept house for his father, afterward, and he remembered his bedroom, with its chintz-covered chairs, and the warm-colored patch quilt on the old cherry bed, and the tan curtains at the windows, edged with dusky red, and the morning sun shining through them. He could almost see them, now.

The Edge of the Knife

The Edge of the Knife Genesis

Genesis A Slave is a Slave

A Slave is a Slave Last Enemy

Last Enemy Uller Uprising

Uller Uprising Ministry of Disturbance

Ministry of Disturbance Time and Time Again

Time and Time Again The Mercenaries

The Mercenaries Police Operation

Police Operation He Walked Around the Horses

He Walked Around the Horses Time Crime

Time Crime Dearest

Dearest Day of the Moron

Day of the Moron Crossroads of Destiny

Crossroads of Destiny Graveyard of Dreams

Graveyard of Dreams The Cosmic Computer

The Cosmic Computer Ullr Uprising

Ullr Uprising Operation R.S.V.P.

Operation R.S.V.P. Rebel Raider

Rebel Raider Murder in the Gunroom

Murder in the Gunroom Space Viking

Space Viking The Answer

The Answer A Planet for Texans (aka Lone Star Planet)

A Planet for Texans (aka Lone Star Planet) Little Fuzzy

Little Fuzzy Four-Day Planet

Four-Day Planet Little Fuzzy f-1

Little Fuzzy f-1 Keeper

Keeper The H. Beam Piper Megapack

The H. Beam Piper Megapack H. Beam Piper

H. Beam Piper Lord Kalvan of Otherwhen

Lord Kalvan of Otherwhen Fuzzy Sapiens f-2

Fuzzy Sapiens f-2 Fuzzies and Other People f-3

Fuzzies and Other People f-3 TIME PRIME

TIME PRIME Fuzzy Sapiens

Fuzzy Sapiens Lord Kalvan of Otherwhen k-1

Lord Kalvan of Otherwhen k-1 The Second H. Beam Piper Omnibus

The Second H. Beam Piper Omnibus