- Home

- H. Beam Piper

Lord Kalvan of Otherwhen k-1 Page 14

Lord Kalvan of Otherwhen k-1 Read online

Page 14

He wondered how many more Princedoms he would have to doom to fire and sword. Not too many-a few sharp examples at the start ought to be enough. Maybe just Hostigos and Nostor, and Sarrask of Sask and Balthar of Beshta could attend to both. An idea began to seep up in his mind, and he smiled.

Balthar's brother, Balthames, wanted to be a Prince, himself; it would take only a poisoned cup or a hired dagger to make him Prince of Beshta, and Balthar knew it. He should have had Balthames killed long ago. Well, suppose Sarrask gave up a little corner of Sask, and Balthar gave up a similar piece of Beshta, adjoining and both bordering on western Hostigos, to form a new Princedom; call it Sashta. Then, to that could be added all western Hostigos south of the mountains; why, that would be a nice little Princedom for any young couple. He smiled benevolently. And the father of the bride and the brother of the groom could compensate themselves for their generosity, respectively, with the Listra Valley, rich in iron, and East Hostigos, manured with the blood of Gormoth's mercenaries.

This must be done immediately, before winter put an end to campaigning. Then, in the spring, Sarrask, Balthar and Balthames could hurl their combined strength against Nostor.

And something would have to be done about fireseed making in the meantime. The revelation about the devils would have to be made public everywhere. And call a Great Council of Archpriests, here at Balph-no, at Harphax City: let Great King Kaiphranos bear the costs-to consider how they might best meet the threat of profane fireseed making, and to plan for the future. It could be, he thought hopefully, that Styphon's House might yet survive.

VERKAN Vall watched Dalla pack tobacco into a little cane-stemmed pipe. Dalla preferred cigarettes, but on Aryan-Transpacific they didn't exist. No paper; it was a wonder Kalvan wasn't trying to do something about that. Behind them, something thumped heavily; voices echoed in the barn-like pre-fab shed. Everything here was temporary-until a conveyor-head could be established at Hostigos Town, nobody knew where anything should go at Fifth Level Hostigos Equivalent.

Talgan Dreth, sitting on the edge of a packing case with a clipboard on his knee, looked up, then saw what Dalla was doing and watched as she got out her tinderbox, struck sparks, blew the tinder aflame, lit a pine splinter, and was puffing smoke, all in fifteen seconds.

"Been doing that all your life," he grinned.

"Why, of course," Dalla deadpanned. "Only savages have to rub sticks together, and only sorcerers can make fire without flint and steel."

"You checked the pack-loads, Vall?" he asked.

"Yes. Everything perfectly in order, all Kalvan time-line stuff. I liked that touch of the deer and bear skins. We'd have to shoot for the pot, on the way south, and no trader would throw away saleable skins."

Talgan Dreth almost managed not to show how pleased he was. No matter how many outtime operations he'd run, a back-pat from the Paratime Police still felt good.

"Well, then we make the drop tonight," he said. "I had a reconnaissance crew checking it on some adjoining time-lines, and we gave it a looking over on the target time-line last night. You'll go in about fifteen miles east of the Hostigos-Nyklos road."

"That's all right. They're hauling powder to Nyklos and bringing back horses. That road's being patrolled by Harmakros's cavalry. We make camp fifteen miles off the road and start around sunrise tomorrow; we ought to run into a Hostigi patrol before noon."

"Well, you're not going to get into any more battles, are you?" Dalla asked.

"There won't be any more battles," Talgan Dreth told her. "Kalvan won the war while Vall was away."

"He won a war. How long it'll stay won I don't know, and neither does he. But the war won't be over till he's destroyed Styphon's House. That is going to take a little doing."

"He's destroyed it already," Talgan Dreth said. "He destroyed it by proving that anybody can make fireseed. Why, it was doomed from the start. It was founded on a secret, and no secret can be kept forever."

"Not even the Paratime Secret?" Dalla asked innocently.

"Oh, Dalla!" the University man cried. "You know that's different. You can't compare that with a trick like mixing saltpeter and charcoal and sulfur,"

THE late morning sun baked the open horse market; heat and dust and dazzle, and flies at which the horses switched constantly. It was hot for so late in the year; as nearly as Kalvan could estimate it from the way the leaves were coloring, it would be mid-October. They had two calendars here-and-now-lunar, for daily reckoning, and solar, to keep track of the seasons-and they never matched. Calendar reform; do something about. He seemed to recall having made that mental memo before.

And he was sweat-sticky under his armor, forty pounds of it-quilted arming-doublet with mail sleeves and skirt, quilted helmet-coif with mail throat-guard, plate cuirass, plate tassets down his thighs into his jackboots, high combed helmet, rapier and poignard. It wasn't the weight-he'd carried more, and less well distributed, as a combat infantryman in Korea-but he questioned if anyone ever became inured to the heat and lack of body ventilation. Like a rich armor worn in heat of day, That scalds with safety. Shakespeare had never worn it himself except on the stage, he'd known plenty of men who had, like that little Welsh pepperpot Williams, who was the original of Fluellen.

"Not a bad one in the lot!" Harmakros, riding beside him, was enthusing. "And a dozen big ones that'll do for gun-horses."

And fifty-odd cavalry horses; that meant, at second or third hand, that many more infantrymen could get into line when and where needed, in heavier armor. And another lot coming in tonight; he wondered where Prince Armanes was getting all the horses he was trading for bootleg fireseed. He turned in his saddle to say something about it to Harmakros.

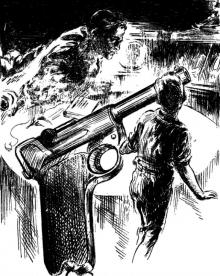

As he did, something hit him a clanging blow on the breastplate, knocking him almost breathless and nearly unhorsing him. He thought he heard the shot; he did hear the second, while he was clinging to his seat and clawing a pistol from his saddlebow. Across the alley, he could see two puffs of smoke drifting from back upstairs windows of one of a row of lodginghouse-wineshop-brothels. Harmakros was yelling; so was everybody else. There was a kicking, neighing confusion among the horses. His chest aching, he lifted the pistol and fired into one of the windows. Harmakros was filing, too, and behind him an arquebus roared. Hoping he didn't have another broken rib, he bolstered the pistol and drew its mate.

"Come on!" he yelled. "And Dralm-dammit, take them alive! We want them for questioning."

Torture. He hated that, had hated even the relatively mild third-degree methods of his own world, but when you need the truth about something, you get it, no matter how. Men were throwing poles out of the corral gate; he sailed past them, put his horse over the fence across the alley, and landed in the littered backyard beyond. Harmakros took the fence behind him, with a Mobile Force arquebusier and a couple of horse-wranglers with clubs following on foot.

He decided to stay in the saddle; till he saw how much damage the bullet had done, he wasn't sure how much good he'd be on foot. Harmakros fung himself from his horse, shoved a half-clad slattern out of the way, drew his sword, and went through the back door into the house, the others behind him. Men were yelling, women screaming; there was commotion everywhere except behind the two windows from which the shots had come. A girl was bleating that Lord Kalvan had been murdered. Looking right at him, too.

He squeezed his horse between houses to the street, where a mob was forming. Most of them were pushing through the front door and into the house; from within came yells, screams, and sounds of breakage. Hostigos Town would be the better for one dive less if they kept at that.

Up the street, another mob was coagulating; he heard savage shouts of "Kill! Kill!" Cursing, he bolstered the pistol and drew his rapier, knocking a man down as he spurred forward, shouting his own name and demanding way. The horse was brave and willing, but untrained for riot work; he wished he had a State Police horse under him, and a yard of locust riot-stick instead of this sword. Then the combination provost-marshal and

police chief of Hostigos Town arrived, with a dozen of his men laying about them with arquebus-butts. Together they rescued two men, bloodied, half-conscious and almost ripped naked. The mob fell back, still yelling for blood.

He had time, now, to check on himself. There was a glancing dent on the right side of his breastplate, and a lead-splash, but the plate was unbroken. That scalds with safety-Shakespeare could say that again. Good thing it hadn't been one of those great armor-smashing brutes of 8-bore muskets. He drew the empty pistol and started to reload it, and then he saw Harmakros approaching on foot, his rapier drawn and accompanied by a couple of soldiers, herding a pot-bellied, stubble-chinned man in a dirty shirt, a blowsy woman with "madam" stamped all over her, and two girls in sleazy finery.

"That's them! That's them!" the man began, as they came up, and the woman was saying, "Dralm smite me dead, I don't know nothing about it!

"Take these two to Tarr-Hostigos," Kalvan directed the provost-marshal. "They are to be questioned rigorously." Euphemistic police-ese; another universal constant. "This lot, too. Get their statements, but don't harm them unless you catch them trying to lie to you."

"You'd better go to Tarr-Hostigos yourself, and let Mytron look at that," Harmakros told him.

"I think it's only a bruise; plate isn't broken. If it's another broken rib, my back-and-breast'll hold it for awhile. First we go to the temple of Dralm and give thanks for my escape. Temple of Galzar, too." He'd been building a reputation for piety since the night of his appearance, when he'd bowed down to those three graven images in the peasant's cottage; not doing that would be out of character, now. "And we go slowly, and roundabout. Let as many people see me as possible. We don't want it all over Hostigos that I've been killed."

AS a child, he had heard his righteous Ulster Scots father speak scornfully of smoke-filled-room politics and boudoir diplomacy. The Rev. Alexander Morrison should have seen this-it was both, and for good measure, two real idolatrous heathen priests were sitting in on it. They were in Rylla's bedroom because it was easier for the rest of Prince Ptosphes's Privy Council to gather there than to carry her elsewhere, they were all smoking, and because the October nights were as chilly as the days were hot, the windows were all closed.

Rylla's usually laughing eyes were clouded with anxiety. "They could have killed you, Kalvan." She'd said that before. She was quite right, too. He shrugged.

"A splash on my breastplate, and a big black-and-blue place on me. The other shot killed a horse; I'm really provoked about that."

"Well, what's being done with them?" she demanded. "They were questioned," her father said distastefully. He didn't like using torture, either. "They confessed. Guardsmen of the Temple-that's to say, kept cutthroats of Styphon's House-sent from Sask Town by Archpriest Zothnes, with Prince Sarrask's knowledge. They told us there's a price of five hundred ounces gold on Kalvan's head, and as much on mine. Tomorrow," he added, "they will be beheaded in the town square."

"Then it's war with Sask." She looked down at the saddler's masterpiece on her leg. "I hope I'm out of this before it starts."

Not between him and Mytron she wouldn't; Kalvan set his mind at rest on that.

"War with Sask means war with Beshta," Chartiphon said sourly. "And together they outnumber us five to two."

"Then don't fight them together," Harmakros said. "We can smash either of them alone. Let's do that, Sask first."

"Must we always fight?" Xentos implored. "Can we never have peace?" Xentos was a priest of Dralm, and Dralm was a god of peace, and in his secular capacity as Chancellor Xentos regarded war as an evidence of bad statesmanship. Maybe so, but statesmanship was operating on credit, and sooner or later your credit ran out and you had to pay off in hard money or get sold out.

Ptosphes saw it that way, too. "Not with neighbors like Sarrask of Sask and Balthar of Beshta we can't," he told Xentos. "And we'll have Gormoth of Nostor to fight again in the Spring, you know that. If we haven't knocked Sask and Beshta out by then, it'll be the end of us."

The other heathen priest, alias Uncle Wolf, concurred. As usual, he had put his wolfskin vestments aside; and as usual, he was nursing a goblet, and playing with one of the kittens who made Rylla's room their headquarters.

"You have three enemies," he said. You, not we; priests of Galzar advised, but they never took sides. "Alone, you can destroy each of them; together, they will destroy you."

And after they had beaten all three, what then? Hostigos was too small to stand alone. Hostigos, dominating Sask and Beshta, with Nostor beaten and Nyklos allied, could, but then there would be Great King Kaiphranos, and back of him, back of everything, Styphon's House.

So it would have to be an empire. He'd reached that conclusion long ago. Klestreus cleared his throat. "If we fight Balthar first, Sarrask of Sask will hold to his alliance and deem it an attack on him," he pronounced. "He wants war with Hostigos anyhow. But if we attack Sask, Balthar will vacillate, and take counsel of his doubts and fears, and consult his soothsayers, whom we are bribing, and do nothing until it is too late. I know them both." He drained his goblet, refilled it, and continued:

"Balthar of Beshta is the most cowardly, and the most miserly, and the most suspicious, and the most treacherous Prince in the world. I served him, once, and Galzar keep me from another like service. He goes about in an old black gown that wouldn't make a good dust-clout, all hung over with wizards' amulets. His palace looks like a pawnshop, and you can't go three lance-lengths anywhere in it without having to shove some impudent charlatan of a soothsayer out of your way. He sees murderers in every shadow, and a plot against him whenever three gentlemen stop to give each other good day."

He drank some more, as though to wash the taste out of his mouth.

"And Sarrask of Sask's a vanity-swollen fool who thinks with his fists and his belly. By Galzar, I've known Great Kings who hadn't half his arrogance. He's in debt to Styphon's House beyond belief, and the money all gone for pageants and feasts and silvered armor for his guards and jewels for his light-o'-loves, and the only way he can get quittance is by conquering Hostigos for them."

"And his daughter's marrying Balthar's brother," Rylla added. "They're both getting what they deserve. The Princess Amnita likes cavalry troopers, and Duke Balthames likes boys."

And he, and all of them, knew what was back of that marriage-this new Princedom of Sashta that there was talk of, to be the springboard for conquest and partition of Hostigos, and when that was out of the way, a concerted attack on Nostor. Since Gormoth had started making his own fireseed, Styphon's House wanted him destroyed, too.

It all came back to Styphon's House.

"If we smash Sask now, and take over some of these mercenaries Sarrask's been hiring on Styphon's expense-account, we might frighten Balthar into good behavior without having to fight him." He didn't really believe that, but Xentos brightened a little.

Ptosphes puffed thoughtfully at his pipe. "If we could get our hands on young Balthames," he said, "we could depose Balthar and put Balthames on the throne. I think we could control him."

Xentos was delighted. He realized that they'd have to fight Sask, but this looked like a bloodless-well, almost-way of conquering Beshta.

"Balthames would be willing," he said eagerly. "We could make a secret compact with him, and loan him, say, two thousand mercenaries, and all the Beshtan army and all the better nobles would join him."

"No, Xentos. We do not want to help Balthames take his brother's throne," Kalvan said. "We want to depose Balthar ourselves, and then make Balthames do homage to Ptosphes for it. And if we beat Sarrask badly enough, we might depose him and make him do homage for Sask."

That was something Xentos seemed not to have thought of. Before he could speak, Ptosphes was saying, decisively

"Whatever we do, we fight Sarrask now; beat him before that old throttle-purse of a Balthar can send him aid."

Ptosphes, too, wanted war now, before Rylla could mount a horse again. Kalvan wondered how m

any decisions of state, back through the history he had studied, had been made for reasons like that.

"I'll make sure of that," Chartiphon promised. "He won't send any troops up the Besh."

That was why Hostigos now had two armies: the Army of the Listra, which would make the main attack on Sask, and the Army of the Besh, commanded by Chartiphon in person, to drive through southern Sask and hold the Beshtan border.

"How about Tarr-Esdreth?" Harmakros asked. "You mean Tarr-Esdreth-of-Sask? Alkides can probably shoot rings around anybody they have there. Chartiphon can send a small force to hold the lower end of the gap, and you can do the same from the Listra side."

"Well, how soon can we get started?" Chartiphon wanted to know. "How much sending back and forth will there have to be first?"

Uncle Wolf put down his goblet, and then lifted the kitten from his lap and set her on the floor. She mewed softly, looked around, and then ran over to the bed and jumped up with her mother and brothers and sisters who were keeping Rylla company.

"Well, strictly speaking," he said, "you're at peace with Prince Sarrask, now. You can't attack him until you've sent him letters of defiance, setting forth your causes of enmity."

Galzar didn't approve of undeclared wars, it seemed. Harmakros laughed. "Now, what would they be, I wonder?" he asked. "Send them Kalvan's breastplate."

"That's a just reason," Uncle Wolf nodded. "You have many others. I will carry the letter myself." Among other things, priests of Galzar acted as heralds. "Put it in the form of a set of demands, to be met on pain of instant war-that would be the quickest way."

"Insulting demands," Klestreus specified. "Well, give me a slate and a soapstone, somebody," Rylla said. "Let's see how we're going to insult him."

"A letter to Balthar, too," Xentos said thoughtfully. "Not of defiance, but of friendly warning against the plots and treacheries of Sarrask and Balthames. They're scheming to involve him in war with Hostigos, let him bear the brunt of it, and then fall on him and divide his Princedom between them. He'll believe that-it's what he'd do in their place."

The Edge of the Knife

The Edge of the Knife Genesis

Genesis A Slave is a Slave

A Slave is a Slave Last Enemy

Last Enemy Uller Uprising

Uller Uprising Ministry of Disturbance

Ministry of Disturbance Time and Time Again

Time and Time Again The Mercenaries

The Mercenaries Police Operation

Police Operation He Walked Around the Horses

He Walked Around the Horses Time Crime

Time Crime Dearest

Dearest Day of the Moron

Day of the Moron Crossroads of Destiny

Crossroads of Destiny Graveyard of Dreams

Graveyard of Dreams The Cosmic Computer

The Cosmic Computer Ullr Uprising

Ullr Uprising Operation R.S.V.P.

Operation R.S.V.P. Rebel Raider

Rebel Raider Murder in the Gunroom

Murder in the Gunroom Space Viking

Space Viking The Answer

The Answer A Planet for Texans (aka Lone Star Planet)

A Planet for Texans (aka Lone Star Planet) Little Fuzzy

Little Fuzzy Four-Day Planet

Four-Day Planet Little Fuzzy f-1

Little Fuzzy f-1 Keeper

Keeper The H. Beam Piper Megapack

The H. Beam Piper Megapack H. Beam Piper

H. Beam Piper Lord Kalvan of Otherwhen

Lord Kalvan of Otherwhen Fuzzy Sapiens f-2

Fuzzy Sapiens f-2 Fuzzies and Other People f-3

Fuzzies and Other People f-3 TIME PRIME

TIME PRIME Fuzzy Sapiens

Fuzzy Sapiens Lord Kalvan of Otherwhen k-1

Lord Kalvan of Otherwhen k-1 The Second H. Beam Piper Omnibus

The Second H. Beam Piper Omnibus