- Home

- H. Beam Piper

Lord Kalvan of Otherwhen k-1 Page 17

Lord Kalvan of Otherwhen k-1 Read online

Page 17

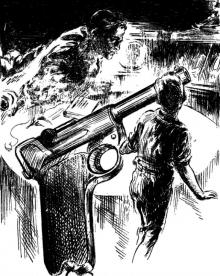

"Dralm knows; I don't. Took to their heels out of this, I suppose." Ptosphes drew one of his pistols and took a powder-flask from his belt. "Watch over my shoulder, will you, Kalvan."

He drew one of his own holster-pair and poured a charge into it. The battle seemed to have moved out of their immediate vicinity, though off in the fog in both directions there was a bedlam of shooting, yelling and steel-clashing. Then suddenly a cannon, the first of the morning, went off in what Kalvan took to be the direction of the village. An eight-pounder, he thought, and certainly loaded with Made-in-Hostigos. On its heels came another, and another.

"That," Ptosphes said, "will be Harmakros."

"I hope he knows what he's shooting at." He primed the pistol, bolstered it, and started on its mate. "Where do you think we could do the most good?"

Ptosphes had his saddle pair loaded, and was starting on one from a boot-top.

"Let's see if we can find some of our own cavalry, and go looking for Sarrask," he said. "I'd like to kill or capture him, myself. If I did, it might give me some kind of a claim on the throne of Sask. If this cursed fog would only clear."

From off to the right, south up the road, came noises like a boiler-shop starting up. There wasn't much shooting-everybody's gun was empty and no one had time to reload-just steel, and an indistinguishable waw-wawwaw-ing of voices. The fog was blowing in wet rags, now, but as fast as it blew away, more closed down. There was a limit to that, though; overhead the sky was showing a faint sunlit yellow.

"Come on, Lytris, come on!" he invoked the weather goddess. "Get this stuff out of here! Whose side are you fighting on, anyhow?"

Ptosphes finished the second of his spare pair, he had the last one of his own four to prime. Ptosphes said, "Watch behind you!" and he almost spilled the priming, then closed the pan and readied the pistol to fire. It was some twenty of the heavy-armed cavalry who had gone in with him. Their sergeant wanted to know where they were.

He hadn't any better idea than they had. Shoving the flint away from the striker, he pushed the pistol into his boot and drew his sword; they all started off toward the noise of fighting. He thought he was still going east until he saw that he was riding, at right angles, onto a line of mud-trampled quilts and bedspreads and mattresses, the things that had been appropriated in the village the night before. He glanced left and right. Ptosphes knew what they were, too, and swore.

Now the battle had made a full 180-degree turn. Both armies were facing in the direction from whence they had come; the route of either would be in the direction of the enemy's country.

Galzar, he thought irreverently, must have overslept this morning. But at least the fog was definitely clearing, gilded above by sunlight, and the gray tatters around them were fewer and more threadbare, visibility now better than a hundred yards. They found a line of battle extending, apparently, due east of Fyk, and came up behind a hodgepodge of militia, regulars and Mobiles, any semblance of unit organization completely lost. Mobile Force cavalry were trotting back and forth behind them, looking for soft spots where breakthroughs, in either direction, might happen. He yelled to a Mobile Force captain who was fighting on foot:

"Who's in front of you?"

"How should I know? Same mess of odds-and-sods we are. This Dralm damned battle…"

Officially, he supposed, it would be the Battle of Fyk, but nobody who'd been in it would ever call it anything but the Dralm-damned Battle.

Before he could say anything, there was a crash on his left like all the boiler-shops in creation together. He and Ptosphes looked at one another. "Something new has been added," he commented. "Well, let's go see."

They started to the left with their picked up heavy cavalry, not too rapidly, and with pistols drawn. There was a lot of shouting-"Down Styphon!" of course, and "Ptosphes!" and "Sarrask of Sask!" There were also shouts of "Balthames!" That would be the retinue Balthar's brother, the prospective Prince of Sashta, had brought to Sask Town-some two hundred and fifty, he'd heard. Then there were cries of "Treason! Treason!"

Now there was a hell of a thing to yell on any battlefield, let alone in a fog. He was wondering who was supposed to be betraying whom when he found the way blocked by the backs of Hostigi infantry at right angles to the battle-line; not retreating, just being pushed out of the way of something. Beyond them, through the thinning fog, he could see a rush of cavalry, some wearing black and pale yellow surcoats over their armor. They'd be Balthames's Beshtans; they were filing and chopping indiscriminately at anything in front of them, and, mixed with them, were green-and-gold Saski, fighting with them and the Hostigi both. All he and Ptosphes and the mercenary men-at-arms could do was sit on their horses and fire pistols at them over the heads of their own infantry.

Finally, the breakthrough, if that was what it had been, was over. The Hostigi infantry closed in behind them, piking and shooting, and there were cries of "Comrade, we yield!" and "Oath to Galzar!" and "Comrade, spare mercenaries!"

"Should we give them a chase?" Ptosphes asked, looking after the Saski-Beshtan whatever-it-had-been.

"I shouldn't think so. They're charging in the right direction. What the Styphon do you think happened?"

Ptosphes laughed. "How should I know? I wonder if it really was treason."

"Well, let's get through here." He raised his voice. "Come on-forward! Somebody's punched a hole for us; let's get through it!"

SUDDENLY, the fog was gone. The sun shone from a cloudless sky; the Mountainside, nearer than he thought, was gaudy with Autumn colors; all the drifting puffs and hanging bands of white on the ground were powder-smoke. The village of Fyk, on his left, was ringed with army wagons like a Boer laager, guns pointing out between them. That was the strong point on which Harmakros had rallied the wreckage of the left wing.

In front of him, the Hostigi were moving forward, infantry running beside the cavalry, and in front of them the Saski line was raveling away, men singly and in little groups and by whole companies turning and taking to their heels, trying to join two or three thousand of their comrades who had made a porcupine. He knew it from otherwhen history as a Swiss hedgehog: a hollow circle bristling pikes in all directions. Hostigi cavalry were already riding around it, firing into it, and Verkan's riflemen were sniping at it. There seemed to be no Saski cavalry whatever; they must all have joined the rush to the south at the time of the breakthrough.

Then three four-pounders came out from the village at a gallop, unlimbered at three hundred yards, and began firing case-shot. When two eight-pounders followed more sedately, helmets began going up on pike-points and caliver muzzles.

Behind him, the fighting had ceased entirely. Hostigi soldiers had scattered through the brush and trampled cornstalks, tending to their wounded, securing prisoners, robbing corpses, collecting weapons, all the routine after-battle chores, and the battle wasn't over yet. He was worrying about where all the Saski cavalry had gotten, and the possibility that they might rally and counterattack, when he saw a large mounted column approaching from the south. This is it, he thought, and we're all scattered to Styphon's House and gone-He was shouting at the men nearest him to drop what they were doing and start earning their pay when he saw blue and red colors on lances, saddle pads, scarves. He trotted forward to meet them.

Some were mercenaries, some were Hostigi regulars; with them were a number of green-and-gold prisoners, their helmets hung on saddlebows. A captain in front shouted a greeting as he came up.

"Well, thank Galzar you're still alive, Lord Kalvan! Where's the Prince?"

"Back at the village, trying to get things sorted out. How far did you go?"

"Almost to Gour. Better than a thousand of them got away; they won't stop short of Sask Town. The ones we have are the ones with the slow horses. Sarrask may have gotten away; we know Balthames did."

"Dralm and Galzar and all the true gods curse that Beshtan bastard!" one of the prisoners cried. "Devils eat his soul forever! The Dralm-damned lackwit cost us the battle, and only

Galzar's counted how many dead and maimed."

"What happened? I heard cries of treason."

"Yes, that dumped the whole bagful of devils on us," the Saski said. "You want to know what happened? Well, in the darkness we formed with our right wing far beyond your left; yours beyond ours, I suppose, from the looks of things. On our right, we carried all before us, drove your cavalry from the field and smashed your infantry. Then this boy-lover from Beshta-we can fight our enemies, but Galzar guard us from our allies-took his own men and near a thousand of our mercenary horse off on a rabbit-hunt after your fleeing cavalry, almost to Esdreth.

"Well, you know what happened in the meantime. Our right drove in your left, and yours ours, and the whole battle turned like a wheel, and we were all facing in the way we'd come, and then back comes this Balthames of Beshta, smashing into our rear, thinking that he was saving the day.

"And to make it worse, the silly fool doesn't shout 'Sarrask of Sask,' as he should have; no, he shouts 'Balthames!'-he and all his, and the mercenaries with him took it up to curry favor with him. Well, great Dralm, you know how much anybody can trust anybody from Beshta; we thought the bugger'd turned his coat, and somebody cried treason. I'll not deny crying it myself, after I was near spitted on a Beshtan lance, and me crying 'Sarrask!' at the top of my lungs. So we were carried away in the rout, and I fell in with mercenaries from Hos-Ktemnos. We got almost to Gour and tried to make a stand, and were ridden over and taken."

"Did Sarrask get away? Galzar knows I want to spill his blood badly enough, but I want to do it honestly."

The Saski didn't know; none of Sarrask's silver-armored personal guard had been near him in the fighting.

"Well, don't blame Duke Balthames too much." Looking around, he saw over a score of Saski and mercenary prisoners within hearing. If we're going to have a religious war, let's start it now. "It was," he declared, "the work of the true gods! Who do you think raised the fog, but Lytris the Weather Goddess? Who confounded your captains in arraying your line, and caused your gunners to overshoot, harming not one of us, but Galzar Wolfhead, the Judge of Princes? And who but Great Dralm himself addled poor Balthames's wits, leading him on a fool's chase and bringing him back to strike you from behind? At long last," he cried, "the true gods have raised their mighty hands against false Styphon and the blasphemers of Styphon's House!"

There were muttered amens, some from the Saski prisoners. Styphon's stock had dropped quite a few points. He decided to let it go at that, and put them in with the other prisoners and let them talk.

PTOSPHES was shocked by the casualties. Well, they were rather shocking-only forty-two hundred electives left out of fifty-eight hundred infantry, and eighteen hundred of a trifle over three thousand cavalry. The body count didn't meet the latter figure, however, and he remembered what the Saski officer had said about Balthames's chase almost to Esdreth Gap. Most of the mercenaries on the left wing had simply bugged out; by now, they'd be fleeing into Listra Valley, spreading tales of a crushing Hostigi defeat. He cursed; there wasn't anything else he could do about it.

Some cavalry arrived from Esdreth Gap: Chartiphon's Army of the Besh men. During the night, they reported, infantry from both the army of the Besh and the Army of the Listra had gotten onto the mountain back of Tarr-Esdreth-of-Sask, and taken it by storm just before daylight. Alkides had moved his three treasured brass eighteen-pounders and some lighter pieces down into the gap, and was holding it at both ends with a mixed force. As the fog had started to blow away, a large body of Saski cavalry had tried to force a way through; they had been driven off by gunfire. Perturbed by the presence of enemy troops so far north, he had sent to find out what was going on. Riders were sent to reassure him, and order him to come up in person and bring his eighteens with him. There was no telling what they might have to break into before the day was over. The long eighteen-pounders were excellent burglar-tools.

Harmakros got off at ten, with the Mobile Force and all the four-pounders, up the main road for Sask Town. All the captured mercenaries agreed to take Prince Ptosphes's colors and were released under oath and under arms. The Saski subjects were disarmed and put to work digging trenches for mass graves and collecting salvageable equipment. Mytron and his staff preempted the better cottages and several of the larger and more sanitary barns for hospitals. Taking five hundred of the remaining cavalry, Kalvan started out a little before noon, leaving Ptosphes to await the arrival of Alkides and the eighteen-pounders.

Gour was a market town of some five thousand. He found bodies, already stripped of armor, in the square, and a mob of townsfolk and disarmed Saski prisoners working to put out several fires, guarded by some lightly wounded mounted arquebusiers. He dropped two squads to help them and rode on.

He thought he knew this section; he'd been stationed in Blair County five otherwhen years ago. He hadn't realized how much the Pennsylvania Railroad Company had altered the face of Logan Valley. At about what ought to be Allegheny Furnace, he was stopped by a picket-post of Mobile Force cavalry and warned to swing right and come in on Sask Town from behind. Tarr-Sask was being held, either by or for Prince Sarrask, and was cannonading the town. While he talked with them, he could hear the occasional distant boom of a heavy bombard.

Tarr-Sask stood on the south end of Brush Mountain, Sarrask's golden-rayed sun on green flying from the watchtower. The arrival of his cavalry at the other side of the, town must have been observed; four bombards let go with strain-everything charges of Styphon's Best, hurling hundred and fifty pound stone cannonballs among the houses. This, he thought, wouldn't do much to improve relations between Sarrask and his subjects. Harmakros, who had nothing but four-pounders, which was to say nothing, was not replying. Wait, he thought, till Alkides gets here.

Battering-pieces, thirty-two-pounders, about six, get cast as soon as Verkan's gang gets foundry going. And cast shells; do something about.

There had been no fighting inside the town; Harmakros's blitzkrieg had hit it too fast, before resistance could be organized. There had been some looting-that was to be expected-but no fires. Arson for arson's sake, without a valid strategic reason as in Nostor, was discountenanced in the Hostigos army. Most of the civil population had either refugeed out or were down in the cellar.

The temple of Styphon had been taken first of all. It stood on almost the exact site of the Hollidaysburg courthouse, a circular building under a golden dome, with rectangular wings on either side. If, as he suspected, that dome was really gold, it might go a long way toward paying the cost of the war. A Mobile Force infantryman was up a ladder with a tarpot and a brush, painting DOWN STYPHON over the door. Entering, the first thing he saw was a twenty-foot image, its face newly spalled and pitted and lead-splashed. The Puritans had been addicted to that sort of small-arms practice, he recalled, and so had the Huguenots. There was a lot of gold ornamentation around; guards had been posted.

He found Harmakros in the Innermost Circle, his spurred heels resting on the high priest's desk. He sprang to his feet.

"Kalvan! Did you bring any guns?"

"No, only cavalry. Ptosphes is bringing Alkides's three eighteens. He'll be here in about three hours. What happened here?"

"Well, as you see, Balthames got here a little ahead of us and shut himself up in Tarr-Sask. We sent the local Uncle Wolf up to parley with him. He says he's holding the castle in Sarrask's name, and won't surrender without Sarrask's orders as long as he has fireseed."

"Then he doesn't know where Sarrask is, either."

Sarrask could be dead and his body stripped on the field by common soldiers-it'd be worth stripping-and tumbled anonymously into one of those mass graves. If so, they might never be sure, and then, every year for the next thirty years, some fake Sarrask would be turning up somewhere in the Five Kingdoms, conning suckers into financing a war to recover his throne. That had happened occasionally in otherwhen history.

"Did you get the priests along with this temple?"

"Oh, yes, Zothnes

and all. They were packing to leave when we got here, and argued about what to take along. We have them in chains in the town jail, now. Do you want to see them?"

"Not particularly. We'll have their heads off tomorrow or the next day, when we find time for it. How about the fireseed mill?"

Harmakros laughed. "Verkan's surrounding it with his riflemen. As soon as we get a dozen or so men dressed in priestly robes, about a hundred more will chase them in, with a lot of yelling and shooting. If that gets the gate open, we may be able to take the place before some fanatic blows it up. You know, some of these under-priests and novices really believe in Styphon."

"Well, what did you get here?"

Harmakros waved a hand about him. "All this gold and fancywork. Then there's gold and silver, specie and bullion, in the vaults, to about fifty thousand gold ounces, I'd say."

That was a lot of money. Around a million US. dollars. He could believe it, though; besides making fireseed, Styphon's House was in the loan-shark business, at something like ten percent per lunar month, compound interest. Anti-usury laws; do something about. Except for a few small-time pawnbrokers, they were the only money-lenders in Sask.

"Then," Harmakros continued, "there's a magazine and armory. We haven't taken inventory yet, but I'd say ten tons of fireseed, three or four hundred stand of arquebuses and calivers, and a lot of armor. And one wing's packed full of general merchandise, probably taken in as offerings. We haven't even looked at that, yet; just put it under guard. A lot of barrels that could be wine; we don't want the troops getting at that yet."

The guns of Tarr-Sask kept on firing slowly, smashing a house now and then. None of the round-shot came near the temple; Balthames was evidently still in awe of Styphon's House. The main army arrived about 1630; Alkides got his brass eighteen-pounders and three twelves in position and began shooting back. They didn't throw the huge granite globes Balthames's bombards did, but they fired every five minutes instead of every half hour, and with something approaching accuracy. A little later, Verkan rode in to report the fireseed mill taken intact. He didn't think much of the equipment-the mills were all slave-powered-but there had been twenty tons of finished fireseed, and over a hundred of sulfur and saltpeter. He had had some trouble preventing a massacre of the priests when the slaves had been unshackled.

The Edge of the Knife

The Edge of the Knife Genesis

Genesis A Slave is a Slave

A Slave is a Slave Last Enemy

Last Enemy Uller Uprising

Uller Uprising Ministry of Disturbance

Ministry of Disturbance Time and Time Again

Time and Time Again The Mercenaries

The Mercenaries Police Operation

Police Operation He Walked Around the Horses

He Walked Around the Horses Time Crime

Time Crime Dearest

Dearest Day of the Moron

Day of the Moron Crossroads of Destiny

Crossroads of Destiny Graveyard of Dreams

Graveyard of Dreams The Cosmic Computer

The Cosmic Computer Ullr Uprising

Ullr Uprising Operation R.S.V.P.

Operation R.S.V.P. Rebel Raider

Rebel Raider Murder in the Gunroom

Murder in the Gunroom Space Viking

Space Viking The Answer

The Answer A Planet for Texans (aka Lone Star Planet)

A Planet for Texans (aka Lone Star Planet) Little Fuzzy

Little Fuzzy Four-Day Planet

Four-Day Planet Little Fuzzy f-1

Little Fuzzy f-1 Keeper

Keeper The H. Beam Piper Megapack

The H. Beam Piper Megapack H. Beam Piper

H. Beam Piper Lord Kalvan of Otherwhen

Lord Kalvan of Otherwhen Fuzzy Sapiens f-2

Fuzzy Sapiens f-2 Fuzzies and Other People f-3

Fuzzies and Other People f-3 TIME PRIME

TIME PRIME Fuzzy Sapiens

Fuzzy Sapiens Lord Kalvan of Otherwhen k-1

Lord Kalvan of Otherwhen k-1 The Second H. Beam Piper Omnibus

The Second H. Beam Piper Omnibus