- Home

- H. Beam Piper

Day of the Moron Page 2

Day of the Moron Read online

Page 2

French Surete testfor mentally deficient criminals. Then there's a memory test, and testsfor judgment and discrimination, semantic reactions, temperamental andemotional makeup, and general mental attitude."

She took the folder and leafed through it. "Yes, I see. I always likedthis Surete test. And this memory test is a honey--'One hen, two ducks,three squawking geese, four corpulent porpoises, five Limerick oysters,six pairs of Don Alfonso tweezers....' I'd like to see some of thesememory-course boys trying to make visual images of six pairs of DonAlfonso tweezers. And I'm going to make a copy of this word-associationlist. It's really a semantic reaction test; Korzybski would have lovedit. And, of course, our old friend, the Rorschach Ink-Blots. I've alwaysharbored the impious suspicion that you can prove almost anything youwant to with that. But these question-suggestions for personal intervieware really crafty. Did Heydenreich get them up himself?"

"Yes. And we have stacks and stacks of printed forms for the writtenportion of the test, and big cards to summarize each subject on. And wehave a disk-recorder to use in the oral tests. There'll have to be apretty complete record of each test, in case--"

* * * * *

The office door opened and a bulky man with a black mustache entered,beating the snow from his overcoat with a battered porkpie hat andcommenting blasphemously on the weather. He advanced into the room untilhe saw the woman in the chair beside the desk, and then started to backout.

"Come on in, Sid," Melroy told him. "Dr. Rives, this is our generalforeman, Sid Keating. Sid, Dr. Rives, the new dimwit detector. Sid's indirect charge of personnel," he continued, "so you two'll be workingtogether quite a bit."

"Glad to know you, doctor," Keating said. Then he turned to Melroy."Scott, you're really going through with this, then?" he asked. "I'mafraid we'll have trouble, then."

"Look, Sid," Melroy said. "We've been all over that. Once we start workon the reactors, you and Ned Puryear and Joe Ricci and Steve Chalmerscan't be everywhere at once. A cybernetic system will only do what it'sbeen assembled to do, and if some quarter-wit assembles one of thesethings wrong--" He left the sentence dangling; both men knew what hemeant.

Keating shook his head. "This union's going to bawl like a branded calfabout it," he predicted. "And if any of the dear sirs and brothers getwashed out--" That sentence didn't need to be completed, either.

"We have a right," Melroy said, "to discharge any worker who is, quote,of unsound mind, deficient mentality or emotional instability, unquote.It says so right in our union contract, in nice big print."

"Then they'll claim the tests are wrong."

"I can't see how they can do that," Doris Rives put in, faintlyscandalized.

"Neither can I, and they probably won't either," Keating told her. "Butthey'll go ahead and do it. Why, Scott, they're pulling the Number OneDoernberg-Giardano, tonight. By oh-eight-hundred, it ought to be coolenough to work on. Where will we hold the tests? Here?"

"We'll have to, unless we can get Dr. Rives security-cleared." Melroyturned to her. "Were you ever security-cleared by any Governmentagency?"

"Oh, yes. I was with Armed Forces Medical, Psychiatric Division, inIndonesia in '62 and '63, and I did some work with mental fatigue casesat Tonto Basin Research Establishment in '64."

Melroy looked at her sharply. Keating whistled.

"If she could get into Tonto Basin, she can get in here," he declared.

"I should think so. I'll call Colonel Bradshaw, the security officer."

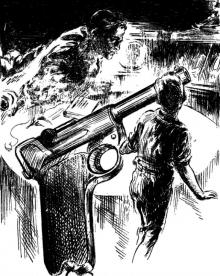

"That way, we can test them right on the job," Keating was saying. "Takethem in relays. I'll talk to Ben about it, and we'll work up some kindof a schedule." He turned to Doris Rives. "You'll need a wrist-Geiger,and a dosimeter. We'll furnish them," he told her. "I hope they don'ttry to make you carry a pistol, too."

"A pistol?" For a moment, she must have thought he was using sometechnical-jargon term, and then it dawned on her that he wasn't. "Youmean--?" She cocked her thumb and crooked her index finger.

"Yeah. A rod. Roscoe. The Equalizer. We all have to." He half-lifted oneout of his side pocket. "We're all United States deputy marshals. Theydon't bother much with counterespionage, here, but they don't fool whenit comes to countersabotage. Well, I'll get an order cut and posted. Beseeing you, doctor."

* * * * *

"You think the union will make trouble about these tests?" she asked,after the general foreman had gone out.

"They're sure to," Melroy replied. "Here's the situation. I have aboutfifty of my own men, from Pittsburgh, here, but they can't work on thereactors because they don't belong to the Industrial Federation ofAtomic Workers, and I can't just pay their initiation fees and uniondues and get union cards for them, because admission to this union is onan annual quota basis, and this is December, and the quota's full. So Ihave to use them outside the reactor area, on fabrication and assemblywork. And I have to hire through the union, and that's handled on amembership seniority basis, so I have to take what's thrown at me.That's why I was careful to get that clause I was quoting to Sid writteninto my contract.

"Now, here's what's going to happen. Most of the men'll take the testwithout protest, but a few of them'll raise the roof about it. Nothingburns a moron worse than to have somebody question his fractionalintelligence. The odds are that the ones that yell the loudest abouttaking the test will be the ones who get scrubbed out, and when the testshows that they're deficient, they won't believe it. A moron simplycannot conceive of his being anything less than perfectly intelligent,any more than a lunatic can conceive of his being less than perfectlysane. So they'll claim we're framing them, for an excuse to fire them.And the union will have to back them up, right or wrong, at least on thelocal level. That goes without saying. In any dispute, the employer isalways wrong and the worker is always right, until proven otherwise. Andthat takes a lot of doing, believe me!"

"Well, if they're hired through the union, on a seniority basis,wouldn't they be likely to be experienced and competent workers?" sheasked.

"Experienced, yes. That is, none of them has ever been caught doinganything downright calamitous ... yet," Melroy replied. "The moron I'mafraid of can go on for years, doing routine work under supervision, andnothing'll happen. Then, some day, he does something on his ownlame-brained initiative, and when he does, it's only at the whim ofwhatever gods there be that the result isn't a wholesale catastrophe.And people like that are the most serious threat facing our civilizationtoday, atomic war not excepted."

Dr. Doris Rives lifted a delicately penciled eyebrow over that. Melroy,pausing to relight his pipe, grinned at her.

"You think that's the old obsession talking?" he asked. "Could be. Butlook at this plant, here. It generates every kilowatt of current usedbetween Trenton and Albany, the New York metropolitan area included.Except for a few little storage-battery or Diesel generator systems,that couldn't handle one tenth of one per cent of the barest minimumload, it's been the only source of electric current here since 1962,when the last coal-burning power plant was dismantled. Knock this plantout and you darken every house and office and factory and street in thearea. You immobilize the elevators--think what that would mean in lowerand midtown Manhattan alone. And the subways. And the new endless-beltconveyors that handle eighty per cent of the city's freight traffic. Andthe railroads--there aren't a dozen steam or Diesel locomotives left inthe whole area. And the pump stations for water and gas and fuel oil.And seventy per cent of the space-heating is electric, now. Why, youcan't imagine what it'd be like. It's too gigantic. But what you canimagine would be a nightmare.

"You know, it wasn't so long ago, when every home lighted and heateditself, and every little industry was a self-contained unit, that a foolcouldn't do great damage unless he inherited a throne or was placed incommand of an army, and that didn't happen nearly as often as ourleftist social historians would like us to think. But today, everythingwe depend upon is centralized, and vulnerable to blunder-damage. Evenour food--remember that poisoned sof

t-drink horror in Chicago, in 1963;three thousand hospitalized and six hundred dead because of one man'sstupid mistake at a bottling plant." He shook himself slightly, asthough to throw off some shadow that had fallen over him, and looked athis watch. "Sixteen hundred. How did you get here? Fly your own plane?"

"No; I came by T.W.A. from Pittsburgh. I have a room at the new

The Edge of the Knife

The Edge of the Knife Genesis

Genesis A Slave is a Slave

A Slave is a Slave Last Enemy

Last Enemy Uller Uprising

Uller Uprising Ministry of Disturbance

Ministry of Disturbance Time and Time Again

Time and Time Again The Mercenaries

The Mercenaries Police Operation

Police Operation He Walked Around the Horses

He Walked Around the Horses Time Crime

Time Crime Dearest

Dearest Day of the Moron

Day of the Moron Crossroads of Destiny

Crossroads of Destiny Graveyard of Dreams

Graveyard of Dreams The Cosmic Computer

The Cosmic Computer Ullr Uprising

Ullr Uprising Operation R.S.V.P.

Operation R.S.V.P. Rebel Raider

Rebel Raider Murder in the Gunroom

Murder in the Gunroom Space Viking

Space Viking The Answer

The Answer A Planet for Texans (aka Lone Star Planet)

A Planet for Texans (aka Lone Star Planet) Little Fuzzy

Little Fuzzy Four-Day Planet

Four-Day Planet Little Fuzzy f-1

Little Fuzzy f-1 Keeper

Keeper The H. Beam Piper Megapack

The H. Beam Piper Megapack H. Beam Piper

H. Beam Piper Lord Kalvan of Otherwhen

Lord Kalvan of Otherwhen Fuzzy Sapiens f-2

Fuzzy Sapiens f-2 Fuzzies and Other People f-3

Fuzzies and Other People f-3 TIME PRIME

TIME PRIME Fuzzy Sapiens

Fuzzy Sapiens Lord Kalvan of Otherwhen k-1

Lord Kalvan of Otherwhen k-1 The Second H. Beam Piper Omnibus

The Second H. Beam Piper Omnibus